What did the Karnataka caste census report recommend on OBC reservations?

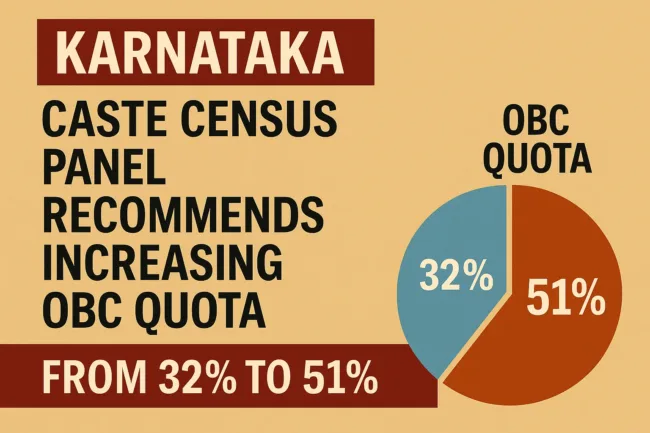

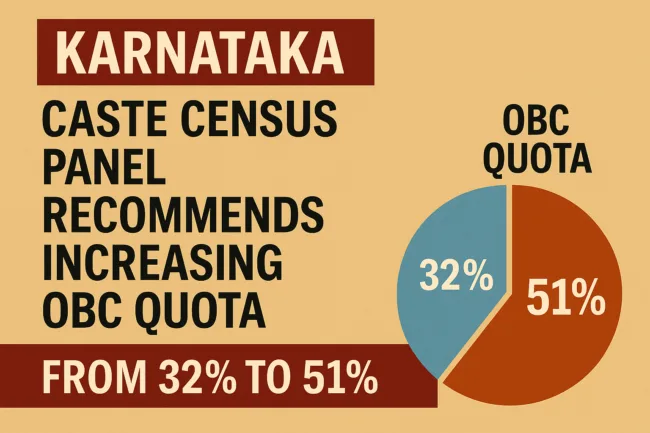

The caste census report presented to the Karnataka Cabinet has proposed a significant overhaul of the state’s reservation framework. The key recommendation suggests raising the existing quota for Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in education and employment from 32% to 51%. If adopted, this would push Karnataka’s total reservation cap to 85%, combining the proposed 51% for OBCs with the existing 24% for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SC/ST) and 10% for Economically Weaker Sections (EWS).

The report is based on the findings of the Karnataka Socio-Economic and Education Survey, commonly known as the caste census. According to the data, OBCs constitute approximately 70% of the state’s population. The commission argues that the current reservation is not proportional to this demographic majority, resulting in what it views as inequitable access to state-sponsored educational and employment opportunities.

Why is Karnataka’s total reservation proposal facing criticism?

The implementation of these recommendations would place Karnataka well beyond the 50% reservation ceiling mandated by the Supreme Court in the landmark Indra Sawhney v. Union of India case in 1992. That verdict, while recognizing the constitutional validity of reservations, set a ceiling on quotas unless “extraordinary circumstances” could justify a higher percentage.

This proposal has immediately become a flashpoint in Karnataka’s political and social landscape. Opposition parties, including the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Janata Dal (Secular) or JD(S), have publicly criticized the caste census process and its findings. R Ashoka, Leader of the Opposition in the Karnataka Legislative Assembly, alleged that the survey lacked scientific rigour and was politically motivated. He claimed that not all households were surveyed and questioned the integrity of the data collection methodology. In his statement, Ashoka said the report was created under the direct influence of the Chief Minister and accused the Congress-led government of attempting to divide communities for electoral advantage.

What is the historical background of Karnataka’s caste survey?

The origins of this caste census can be traced back to Siddaramaiah’s first term as Chief Minister in 2014, when he commissioned the Karnataka Socio-Economic and Educational Census. That survey was conducted by a committee led by then-chairman of the Backward Classes Commission, H. Kantharaju, at a cost of approximately ₹169 crore. Despite the substantial investment and large-scale data collection effort, the report was never made public or discussed in the Cabinet and remained in cold storage for nearly a decade.

It was only after Siddaramaiah returned to power in 2023 that momentum around caste-based data resurfaced. The findings were finally tabled in February 2024 and were officially presented during a Cabinet meeting on April 12, 2025. The government has announced a special session on April 17 to discuss the recommendations and decide on the way forward.

What is the rationale behind increasing the OBC reservation to 51%?

The commission backing the caste census has argued that the share of reservations should reflect the population proportion of the communities involved. It pointed out that although backward classes make up nearly 70% of Karnataka’s population, they are currently allotted only 32% reservation. It claimed this disparity undermines equal opportunity in accessing public education and government employment.

The panel emphasized that “reservation in proportion to population” is the most viable mechanism to ensure equitable distribution of government benefits. The report noted that despite the increase in the OBC population, more than half of Karnataka’s population is excluded from adequate representation under the current quota system.

In addition to raising the OBC quota, the panel recommended introducing horizontal reservation—a system that allocates sub-quotas across categories such as women, persons with disabilities, and ex-servicemen within the broader vertical reservations. This would further stratify how benefits are distributed within each category, theoretically improving access for underrepresented sections within castes and communities.

How have dominant communities reacted to the report?

The proposal has not gone unchallenged by powerful caste groups. The Lingayats and Vokkaligas—two socially and politically influential communities in Karnataka—have expressed dissatisfaction with the caste survey’s findings. They allege that the data underrepresents their population figures, possibly leading to a reduction in their share of reservation benefits.

Their opposition is particularly significant given their electoral influence across key constituencies in Karnataka. Both groups are traditionally seen as vote banks for the BJP and JD(S), and their discontent could affect the political calculus heading into future elections. These groups fear that a redistribution of quotas based on potentially flawed data could undermine their historical advantages in education and employment.

What are the legal and constitutional hurdles in implementing the recommendations?

The major legal obstacle remains the 50% cap on reservations established by the Supreme Court. While Tamil Nadu has long maintained a reservation rate above this limit, its laws were included in the Ninth Schedule of the Constitution to protect them from judicial review. Karnataka would likely face intense legal scrutiny unless similar constitutional safeguards are enacted.

Moreover, any legislation to increase reservations would need to survive judicial review at both the state and central levels. Critics argue that implementing 85% reservation would be vulnerable to legal challenges unless supported by airtight empirical evidence and a compelling rationale that demonstrates extraordinary social circumstances.

Legal experts have pointed out that without central legislation or a constitutional amendment, Karnataka’s move could face the same fate as similar quota expansions in Maharashtra and Haryana, both of which were struck down by the judiciary.

How has the Karnataka government responded to the opposition?

Chief Minister Siddaramaiah has defended the caste census as a scientific and necessary exercise for social justice. He affirmed that the government “has accepted the report and will implement it.” Siddaramaiah’s stance reflects the Congress Party’s broader strategy of using caste-based data to recalibrate welfare distribution and electoral messaging.

His administration appears committed to pushing through the recommendations, citing the historical neglect of backward classes and the need for data-backed governance. By promising to act on the findings, the government is signalling its alignment with inclusive development narratives and aiming to consolidate support among OBC voters, who constitute a decisive demographic in Karnataka’s political landscape.

What could be the broader implications for Indian politics?

If Karnataka successfully implements the 51% OBC reservation, it could set a precedent for other states considering similar expansions. The move could also reignite the national debate over the need for an updated caste census at the central level. The last such comprehensive exercise was carried out in 1931, and since then, caste data in India has remained largely undocumented, with the exception of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Calls for a national caste census have been growing louder, with political parties across the spectrum expressing support, especially ahead of the 2024 general elections. The Karnataka model could serve as a test case for how caste-based data is used to formulate policy—and how it reshapes the reservation discourse across India.

At the same time, the move risks deepening divisions among communities and raising legal questions about constitutional limits and equality under law. The balancing act between social justice and legal viability will likely determine the fate of the proposal.

As Karnataka prepares for a special Cabinet meeting on April 17, the state’s decision on whether to adopt the caste panel’s recommendations will be closely watched across the country for its social, legal, and political consequences.

Discover more from Business-News-Today.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.