The European Union is no longer limiting its semiconductor strategy to logic chips, legacy foundries, or trailing-edge fabrication. Its recent approval of €450 million in Czech State aid to support Onsemi’s integrated silicon carbide manufacturing plant in Rožnov pod Radhoštěm signals a shift toward power semiconductors that are essential to the continent’s electrification goals. With the new facility expected to be operational by 2027, policymakers and industry leaders are asking a sharper question: can silicon carbide help make Europe truly self-reliant in the electric vehicle and clean energy supply chain?

For the European Commission, this marks one of the most strategically consequential uses of public capital under the European Chips Act to date. The facility is the first of its kind in the region, designed to cover the entire silicon carbide value chain from crystal growth through to finished power devices. With rising geopolitical risk and tightening semiconductor exports globally, Europe’s bet on silicon carbide may determine whether it can independently support its green and digital transition targets by 2030.

Why silicon carbide is emerging as the key to Europe’s clean technology infrastructure

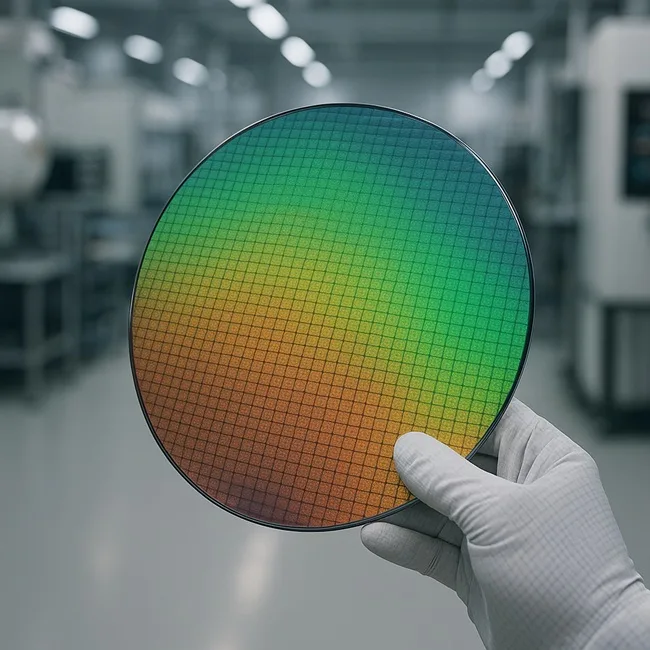

Silicon carbide is not just a better-performing semiconductor. It is becoming indispensable to high-power, high-efficiency electronics in electric vehicles, ultrafast charging stations, renewable power inverters, and high-voltage industrial equipment. Unlike conventional silicon chips, silicon carbide devices offer higher thermal conductivity, lower switching losses, and the ability to handle extreme voltage levels, making them ideally suited to decarbonization and grid modernization efforts.

This performance leap is what has made silicon carbide the substrate of choice for traction inverters in EVs, for solar and wind power converters, and increasingly for aerospace and data center power systems. European policymakers now view the technology as mission-critical, not just to competitiveness, but to sovereignty. However, most of the global silicon carbide substrate and device supply has historically come from the United States and Japan, with growing capacity in China. Until now, Europe lacked a fully integrated silicon carbide manufacturing plant that could support domestic demand at industrial scale.

Onsemi’s planned €1.64 billion investment in Czechia, partially funded by the €450 million State aid package approved by the European Commission in November 2025, addresses this shortfall directly. The Rožnov pod Radhoštěm plant is expected to begin commercial production in 2027 and is designed to manufacture 200 mm silicon carbide devices through a fully integrated flow, covering everything from raw crystal growth to final device packaging.

How Onsemi’s Rožnov facility fits into Europe’s broader silicon carbide strategy

The European Chips Act, which entered into force in September 2023, aims to mobilize more than €43 billion in semiconductor investments and increase the European Union’s share of global chip production to at least 20 percent by 2030. While most headline projects have focused on logic and memory chips, including Intel’s expansion in Magdeburg and the STMicroelectronics and GlobalFoundries joint project in France, silicon carbide is now taking center stage in the energy transition narrative.

The Onsemi facility is Europe’s first silicon carbide fab to meet the definition of a fully integrated production facility under the European Chips Act. That includes crystal growth, epitaxy, wafer fabrication, and final assembly on a single site. Onsemi has formally applied for its recognition under the Chips Act, which would allow the plant to receive priority status in the event of semiconductor shortages and bind the company to certain European supply commitments.

European Union officials highlighted that the project addresses a clear funding gap and would not have been pursued in Europe without State aid. The grant was approved under Article 107(3)(c) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. According to the Commission’s assessment, the aid package is necessary, proportionate, and limited to the minimum amount required to trigger the investment, with an upside profit-sharing mechanism in place for Czechia if returns exceed expectations.

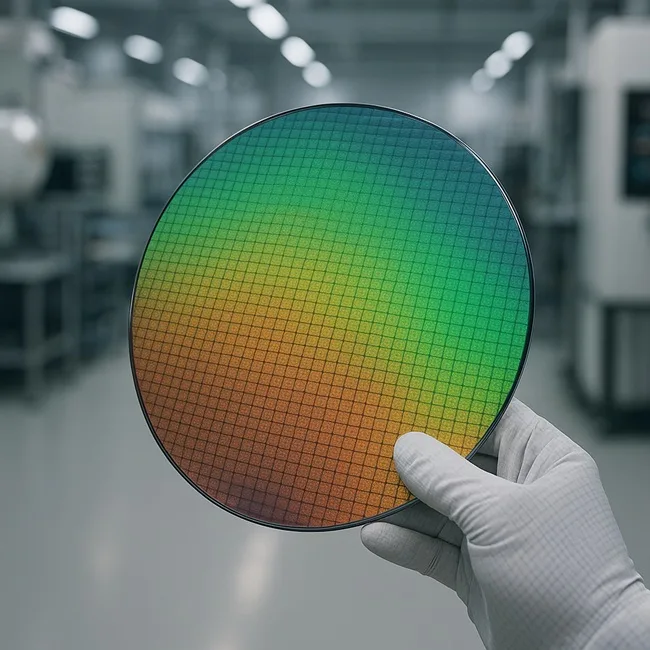

What silicon carbide capacity Europe needs to support EV and energy resilience goals

Europe’s electric vehicle and energy sectors are expected to require exponentially more silicon carbide capacity in the coming decade. Analysts estimate that by 2030, the region will need more than 200,000 200 mm silicon carbide wafers per month to meet demand from automotive original equipment manufacturers, grid developers, and industrial clients. Current European capacity is significantly below that threshold, and global silicon carbide supply remains tight, especially for 200 mm wafers.

The Rožnov facility will help address this imbalance, but it will not be enough on its own. Wolfspeed is currently building a silicon carbide device and substrate plant in Saarland, Germany, and STMicroelectronics is expanding its 200 mm capacity at sites in Catania and Agrate. Other players such as Soitec and X-FAB are also developing silicon carbide process nodes, though often without full vertical integration.

Europe’s strategy increasingly revolves around building sovereign capability across the entire value chain. That means securing not only fabrication but also upstream substrate supply and downstream design and packaging expertise. Onsemi’s vertically integrated approach at Rožnov could serve as a blueprint for future projects. The plant’s ability to grow silicon carbide crystals in-house is particularly significant, as this is one of the most capital-intensive and technically demanding steps in the entire process.

Can European silicon carbide fabs compete with China and the United States?

The silicon carbide landscape is fast evolving into a geopolitical race. In the United States, Onsemi and Wolfspeed are both expanding aggressively, with Department of Energy and Department of Defense support. In China, firms such as San’an and StarPower have received large-scale government backing and are rapidly scaling 200 mm silicon carbide capacity. Japan’s Showa Denko and Rohm Semiconductor remain key global suppliers of wafers and modules.

European companies like STMicroelectronics have a strong device-level footprint, but the region historically lacked substrate production and full-stack control. The European Chips Act is designed to close that gap, but time is running short. If the European Union is to achieve 20 percent of global chip output and strategic independence in electrification semiconductors, it will need to scale silicon carbide fabs quickly and secure long-term raw material supply agreements.

Onsemi’s Czech site, with its high integration and proximity to Germany’s automotive hub, offers a strategic foothold. Analysts expect it to serve as a regional anchor for both electric vehicle and grid-tied applications. However, the plant’s success will depend on downstream industry alignment. European automakers, utilities, and energy storage providers will need to commit to regional sourcing and co-develop design and testing ecosystems around these new fabs.

Will European demand match domestic SiC capacity buildout?

The European electric vehicle market is forecast to exceed 50 percent of new vehicle sales by 2030, with several member states aiming for full internal combustion engine phase-out by 2035. These targets translate into massive silicon carbide module requirements for drivetrain inverters, onboard chargers, and fast-charging infrastructure.

At the same time, the European Union’s clean energy goals call for large-scale integration of solar and wind energy, all of which require high-efficiency conversion and grid stabilization solutions — areas where silicon carbide plays a central role.

Yet European industrial buyers have historically relied on global sourcing. Wolfspeed’s recent supply deals with German automotive suppliers are a sign that sentiment is shifting. STMicroelectronics has long supported Renault and Stellantis with power electronics, but more institutional commitment is needed. Onsemi’s new fab could be a catalyst for deeper European supply chain integration — if local demand is secured.

What must happen next to ensure Europe’s silicon carbide self-reliance?

Europe’s road to silicon carbide sovereignty will not be determined by this single project. Onsemi’s Czech facility is a vital pillar, but it must be accompanied by policy support across education, R&D, packaging, and supply chain coordination. Workforce development programs to train engineers in wide-bandgap semiconductor fabrication are especially urgent.

Moreover, national governments will need to align permitting processes, industrial energy pricing, and infrastructure readiness to prevent fab delays. Projects like Rožnov can only deliver full strategic value if linked to a broader network of European chip capabilities, from Dresden to Catania.

The next 24 months will determine whether the European Union can scale a complete, vertically integrated, and self-reinforcing silicon carbide ecosystem. Without it, the continent may meet its climate targets, but only by relying on non-European hardware.

Discover more from Business-News-Today.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.